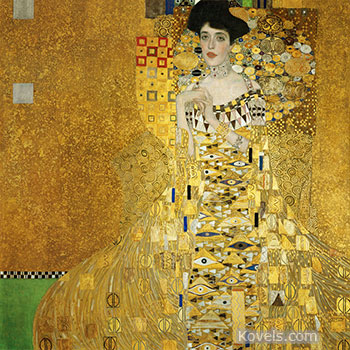

Plundered treasures, paintings, sculptures, gold, and more were taken by ancient Greeks, Romans, medieval Crusaders, and armies for centuries as prizes of war. No one returned them so the art went to museums and private collections. By World War I, there was concern about the legality of theft. By the end of World War II, lawsuits chasing the Nazi’s stolen art had started. Governments agreed that if the prewar owners were found, the art must be returned. But the statutes of limitations made recovery difficult and expensive. In 2016, the Holocaust Expropriated Art Recovery (HEAR) Act was signed into law. It should help. A surviving relative with proof a piece was stolen or part of a forced sale by Nazis can sue to get it back for six years from the day of “actual discovery.” Museums, auction houses and galleries now check pieces without provenance (history) for the years 1933 to 1945. They might be part of the over 650,000 pieces known to be taken for Hitler, Goring, and Nazi projects. The Gustav Klimt painting of Adele Bloch-Bauer featured in the movie Woman in Gold was awarded to a niece of the Austrian owner. She sold it for $135 million. Some museums will not do research that might prove their pieces are “Holocaust art.” This year, there is a lawsuit involving the Norton Simon Museum in California and two Cranach paintings the family claimed were taken by Goring. And HEAR is involved in a fight by an heir for two Egon Schiele drawings that are owned by a London dealer. They are worth about $5 million. Few of us will buy a million-dollar painting, but missing examples are still to be found, returned, and sold.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.