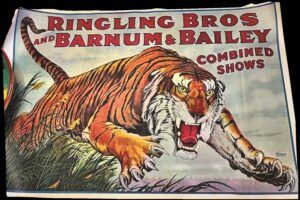

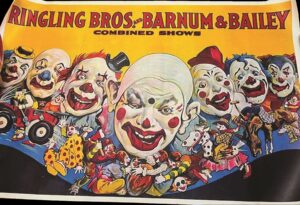

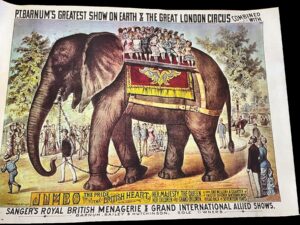

Collector’s Gallery: Circus Poster Trio

Q: My father bought these posters in the 1970s and never framed them. They are 23.5 inches by 36 inches. My mom wants to sell them. Can you tell me their worth and where we could sell them?

A: When trying to identify original circus posters from the many reproductions, there are several things to consider. There are certain key indicators of authenticity. My dad owned and operated a printing firm in Manhattan for many years, and I learned a great deal about printing as a kid. First, we can look at the printing and paper quality and look for signs of vintage printing techniques. Original circus posters were printed using lithography on thin paper and were often distributed folded, so you may see fold lines or creases. Reproductions are usually printed on heavier, glossier paper, which feels different to the touch compared to the lightweight, sometimes brittle stock used for vintage posters. Under magnification, original lithographic posters will not look pixelated, whereas modern digital reproductions may show pixelation or dot patterns.

Date tags and show information are another way to distinguish original posters. Original circus posters often had date tags or smaller papers pasted on them indicating the day, date, and location of the show. However, these tags are sometimes missing or partially torn off. Reproductions may have a copyright date, the word “reproduction,” or an order number (sometimes prefaced with “P”) printed in the lower corner. Occasionally, these markings may be trimmed off.

The posters should also be examined for signs of age. Original circus posters will show natural signs of aging, such as yellowing, minor creasing, and wear along the edges. Early-era posters were usually folded. An “original” poster without fold lines is likely a reproduction.

Lastly, and more importantly, in the case of your posters, we look at the size. Authentic vintage circus posters were typically printed in standard sheet sizes. The most common is the one-sheet, which measures 28 inches by 42 inches, and the half-sheet, which is 28 inches by 21 inches or 42 inches by 14 inches. Other sizes (multiples of sheets) were also used, but these two are the most prevalent.

Many reproductions are not printed in these standard sizes. For example, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey sold reproductions in sizes such as 24 inches by 17 inches or, as in the case of your posters, 23.5 inches by 36.25 inches.

While I am unable to examine your posters for printing technique or signs of age, I am fairly certain, based on their size, that they are late 20th-century reproductions with a value in the $20.00 to $30.00 range.

Our guest appraiser is Dr. Anthony Cavo, a certified appraiser of art and antiques and a contributing editor to Kovels Antique Trader. Cavo is also the author of Love Immortal: Antique Photographs and Stories of Dogs and Their People.

Do you have a question for Collector’s Gallery? Send your question and photos via e-mail to ATNews@aimmedia.com. Please include as much pertinent information about your item as possible, including size, condition, history and anything else that might help in identifying and valuing your item.

Arnold Rothstein

Arnold Rothstein