Dear Lee,

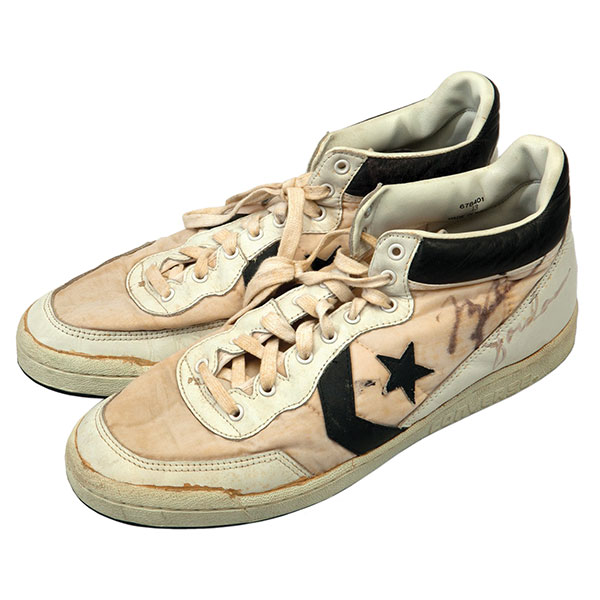

During the past month, the news has informed us of record prices in the stock market, record prices in the art market, and the newest economic “bubble” — sneaker collecting — which is growing and making money.

We first wrote about sneaker collecting in 2010. We first used the term “sneakerheads” in 2017. Sneakerheads are collectors who invest in new, used, rare or limited high-end sneakers. Many hold them for a year or more, then sell them for a profit. It requires watching sneaker “stock market” prices morning and night and timing sales just right.

But now sneaker trading has become huge in China and it is worrying more traditional investors. China is worried that demand for import sneakers may end and prices will start to go down. Investing “bubbles” like this can cause huge loses and bankruptcy because they end suddenly. China recently has had bitcoin, garlic and even crab futures bubbles. Sneaker traders have tried to set up platforms to help identify fakes and eliminate some loopholes, but there are time lags that crafty traders can exploit to cancel or bid. Buyers must take delivery of already-inspected sneakers before they can sell them, but they are still allowed to buy some announced new-to-market sneakers before they even go on sale.

Collectors beware. Learn from the history of what was probably the first “bubble” — Tulipmania — the crazy ups and downs in the price of tulip bulbs in Holland from 1633 to 1637. Hybrid tulips were developed in amazing color combinations and were important features of the Dutch garden. They were almost all originally one of a kind and a sign of wealth and social standing. Tulipmania started when a house was traded for three tulip bulbs. Before that, bulbs had been traded among growers. Florists bought and sold bulbs still in the ground. They became so popular, they were used as collateral for loans, but without inspection of the bulbs or even proof they were real. Promissory notes and other payment methods outside of government banking were used. Speculators bought the bulbs even though there was no way to settle payment disputes. In January 1637, some florists sold their investments and other investors noticed. By February, an auction of bulbs had no bids. Lowered prices still couldn’t attract bidders. It set off a crash with panicked investors selling at any price. Bulb prices went down to 1 to 5 percent. Many investors went bankrupt because of the loses.

At first in 2010, buyers could get sneakers from the stores on the first day of release. Today it is by lottery, and sneakerheads must pay lucky owners a higher price.

What will happen in the United States? Remember the swift fall of Ty Beanie Babies, collector plates, limited edition ingots and medals, and other company-produced rarities. Limited edition plates now cost only a few dollars and only about three vintage Ty animals are wanted by collectors.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.