Identification Guides

Tableware

The twentieth century saw astounding changes in the American home and American food. The nineteenth-century housewife killed the chicken, plucked its feathers, and cleaned, cut, seasoned, and cooked the chicken on an open flame. By 1990 she went to a grocery store and bought either a heat-and-serve prepared meal or a cut-up and cleaned chicken ready to cook quickly in the oven. In the early 1900s, refrigerated railroad cars made just a few out-of-season fruits and vegetables available. By the 1950s, frozen food technology made vegetables and fruit from the United States and other countries available year round. These changes required new dishes for different ways of cooking and serving. At the beginning of the century, luxuries like fresh asparagus were served with tongs on special oblong dishes, and grapes were served in special baskets with grape scissors. To evaluate and date twentieth-century tableware, it is necessary to consider not only the different styles of design, but also the changes in food preparation, household help, lifestyle, fads, and the worldwide economics of manufacturing dinnerware.

The middle-class American family in 1900 had servants and many children. They lived in a large house without electricity. Formal family sit-down dinners were the rule, with many courses and correct special dishes and serving pieces for each course. The dishes used for important holiday or party entertaining might be made in France, England, Germany, Japan, or the United States. The most popular “best” dishes were French Haviland. Everyday dishes were probably ironstone from the United States, England, Germany, or Asia, some plain white, some decorated with transfer designs or decal decorations.

World War I cut off the supply of dishes from Germany and Japan. Americans bought everyday sets made in Ohio, West Virginia, or New Jersey. After the war, families wanted to buy new furniture and dishes for new homes. New ways to entertain came into fashion and influenced the market for tableware. In the 1920s, bridge parties were popular, and card players were served on bridge-table sets of dishes: four place settings often decorated with cards. The snack plate, a large plate with a space to hold a matching cup, was a new form. Dinner dishes were sold in smaller sets, eight instead of twelve place settings, because dining rooms and dining tables were smaller. The cocktail party was another fashionable way to entertain, even in the days of Prohibition. Cocktail shakers, martini pitchers, and all sorts of bar paraphernalia were created.

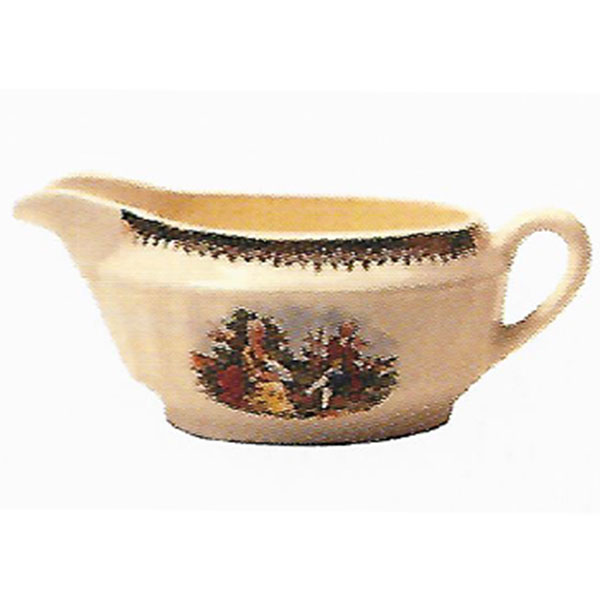

In the 1930s, spaghetti sets were introduced. The set included a large covered serving bowl, six small bowls and a separate dish for grated cheese. Corn-on-the-cob sets became popular. A set of long narrow bowls, often decorated to look like ears of corn, was sold with a large serving bowl. Deviled-egg plates with sections shaped for egg halves were introduced. Dishes designed specifically for a holiday like Thanksgiving or Christmas were marketed. In 1938 the English firm Spode made the first dinnerware set decorated with a Christmas tree. Other companies soon followed. A large turkey platter decorated with Thanksgiving scenes was available from many companies, even those in countries that did not celebrate Thanksgiving.

The 1940s and ’50s saw the family eating together in the dining room at a table set with tablecloth and napkins, matching dishes and silverware. But entertaining became less formal. Groups gathered to talk, play games like bridge, canasta, and Scrabble, and munch snacks, perhaps from the new chip-and-dip set. Friends and neighbors held progressive dinners, going from house to house, each hostess serving a course in special dishes. After the end of World War II in 1945, the returning servicemen and their families needed new houses and furnishings. Acres of tract homes like Levittown on Long Island offered one-story, affordable houses with one living-dining area, not two separate rooms, and very simple woodwork and walls. This new type of home and the lack of household help led to entertaining with buffet dinners. Ceramic and metal casseroles were made to both cook and serve food. Modern shapes were created for dishes. Rimless plates that could be stacked on a buffet table and easy-to-hold cups became popular. Mix-and-match colors made it easier to buy dishes a few at a time. American Modern dinnerware by Russel Wright or Homer Laughlin’s solid-color Harlequin dishes were the first choice of most newlyweds. Stores promoted the idea of breakfast sets, luncheon sets, and dinner sets of dishes. Casual designs were preferred. Grilling outdoors led to many new serving pieces, like sets of forks and tongs for the grill. Cocktail parties continued to be favored, and new mixed drinks were invented, including the Moscow Mule served in the proper copper mug and South Seas fruit drinks served in Tiki-shaped pottery glasses. In 1954 Swanson introduced the first TV dinner in a foil tray, and dinner and dinner dishes have never been the same.

In the 1960s, dishes and glassware were still sold in sets of eight to keep prices low, but open stock made it possible to add to the set later. Chip-and-dip sets were still popular. All of the special dishes of the 1930s, like deviled-egg plates and corn-on-the-cob sets, were back. So were progressive dinners, cocktail parties, and cookouts. Television changed the eating habits of the nation, and many families ate while watching a favorite show. But the most unexpected change was that interest in gourmet cooking returned with Julia Child’s television show, The French Chef, which encouraged sophisticated cooking, wine tasting, and proper dishes for cooking and eating. Contemporary pottery seemed suitable for this type of dinner. Very expensive, artistic dinnerware like those by the German company Rosenthal were made and sold to the wealthy, and formal dinner parties returned. There was little emphasis on ethnic or healthier foods at this time.

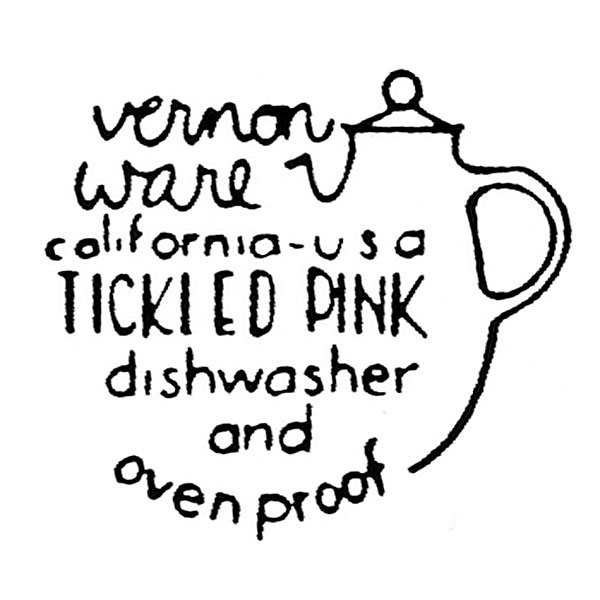

The automatic dishwasher (invented in 1946) and microwave (invented in 1955) became standard kitchen appliances by the 1970s. Dishes had to be made with no gold trim because it sparked in the microwave. Sturdy edges on plates avoided chipping in the dishwasher.

The 1980s and ’90s saw quick dinners, often with prepared foods or restaurant-prepared fast-food. Ethnic foods, quick meals, health food, and gourmet cooking all became popular subjects for television shows and helped expand the eating tastes of Americans. Family meals on weekdays became harder to schedule because children had more and more after-school activities. Weekends and holidays were the time for family dinners and fancy table settings. Heirloom dishes and unmatched groups of dishes were favored to create “an individual look.”

|

|

|

| Dot is the name of the pattern on this Hall China cook-and-serve casserole that kept food hot for the dinner or buffet table. It is part of the Gold Label line made in the mid-1950s. | Great-grandmother's set of Haviland china was saved for parties and important dinners. The thin, white porcelain decorated with flowers or gold rims was more elegant than heavy ironstone. This covered serving dish is marked Theodore Haviland, Limoges, France, a mark used after 1893. | Ironstone dishes and teapots were made in Europe and the United States. They were usually white with raised decorations of leaves, wheat, or scrolls. Some ironstone had added transfer decorations, usually blue or black. |

|

|

|

| The Spode Christmas pattern sold so well it started the tradition of special designs on holiday dishes. | Ever sit with a plate filled with food in one hand and a cup of coffee in the other while trying to eat in a crowded room at a friend's party? In 1944 this Blue Ridge Fruit Fantasy snack set was designed to solve the problem, a popular idea even today. | The ad says it all—china for the carefree way of life. Rimless plates had the newest look but made eating a bit more difficult. The peas slid across the plate and, with no rim as a barrier, fell on the table. |