Identification Guides

Glass

Almost everyone has a piece of old glass that has been in the family for years, and every piece seems to have a glamorous history behind it. Most of the stories are more fable than fact. There were stories in our own family about six green glasses that had belonged to our grandfather. Each grandchild was given one of the priceless green glasses with the wonderful story of its rarity. We finally looked up the priceless glasses and learned the green pressed glass with its gold decorations was a pattern called “Four Petal.” It was made for the Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company about 1890 and given away free with the purchase of coffee. We still display Grandpa’s green glasses in a special place and fondly recall the fantastic stories of the “rare” green glass. Our heirloom is just another piece of glass that has now become old enough to be considered an antique, but too ordinary to be considered priceless.

The study of glass requires time and effort. Colored glass was not popular until after the Civil War. Of course, some colored glass was made earlier, and many eighteenth-century pieces were produced from aqua, amethyst, olive, or green glass; but glassmakers focused their efforts on making glass look like rock crystal—as clear as possible—until about 1860. After that time, many new types of colored glass were developed.

To identify glass, it helps to understand the basic methods of manufacture and a few of the technical terms. The basic materials that are used to make glass, such as sand and various alkalis, are measured and mixed together to form a batch. The batch is heated and the resulting molten glass is called metal (which can be very confusing). When the “metal” reaches the appropriate temperature, the glassworker gathers a blob of glass with a blowpipe. The blob, called a gather, is inflated by blowing through the blowpipe, then transferred to a pontil (also called a punty rod). After the item is shaped with paddles and tools, it is removed from the pontil. A rough spot, called a pontil mark, is often left on the bottom of the item where the pontil was attached.

There are many ways to shape glass. Ancient glass was shaped around a solid ceramic core or with a blowpipe. The earliest blown glass was free-blown, meaning that all of the shaping was done by hand. Since decoration was added by shaping with tools or by engraving, the finished item was a unique luxury item.

The next type of glassmaking was pattern-molding. German glassmakers used dip-molds to add a design to glass as early as 1400. American glassmakers were using the technique by the late 1700s. The glass was blown into a small cylindrical mold, sometimes hinged, with an interior pattern. When the glass was removed, heated again, and blown to the desired size, the impression of the mold remained on the glass. The finished piece had geometric swirls, ribs, or designs like diamonds or feathers. The swirls on the finished piece were smaller at the ends because the blowing process “stretched” the design at the center. Imagine a design drawn on a toy rubber balloon. As it is blown larger, it distorts in much the same way as the swirls of blown-molded glass. Because the items still required shaping, pattern-molded glassmaking was still expensive.

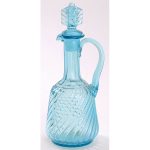

The use of the three-piece mold between 1820 and 1880 increased the availability of glassware in the United States. Hot glass was blown into full-size molds with two to four hinged parts that shaped items from top to bottom. Very little offhand work was required to finish the piece. Three-piece mold-blown items can be recognized by the “seams” created by the edges of the mold parts.

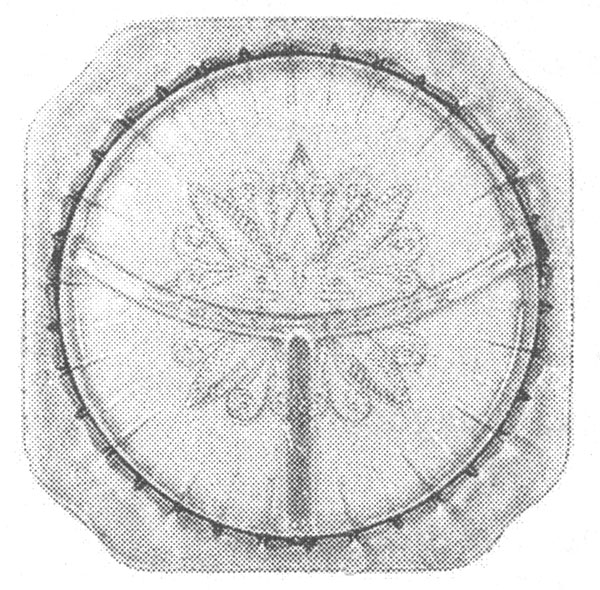

The invention of the mechanical press in the mid 1820s meant glass could be made inexpensively. Instead of blowing hot glass into a shape, it was pressed into a mold with a weight. A pressed glass item takes on the design and shape of the mold. Many patented pressing processes were developed in the mid-nineteenth century. Pressed glass tableware is the easiest glassware to identify. Companies made dishes and accessories in their own patterns. Many of them are named in advertisements and catalogs.

|

|

|

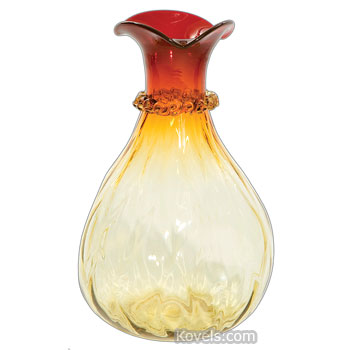

| Photo: American Bottle Auctions | ||

| Our family’s “famous” Delaware pattern emerald green tumbler has worn gold trim. It is was part of a set of six glasses and a water pitcher. | This free-blown creamer with applied handle and foot is in the Twelve Diamond pattern. It has a pontil scarred base. It was probably made at a Midwestern glass house. (Photo: American Bottle Auctions) | This cruet, probably made in England, was made in a three-piece mold. It has a pressed glass stopper. The cruet holds eight ounces of liquid. It was made between 1860 and 1890. |